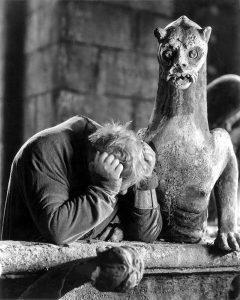

Why Was I Not Made of Stone Like Thee?

One of the highlights of Charles Laughton’s moving performance in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) comes at the end of the film. Lovelorn for Esmerelda, Quasimodo asks one of Notre Dame’s famed gargoyles, “Why was I not made of stone like thee?” Broken hearts aside, we can relate: our restoration practice requires—and fosters—architectural empathy, a sensitivity for the inherent quality of materials and the value of historic fabric.